Welcome to our Book of the Month club!

Each month, we invite you to read a new and exciting book, hand-chosen by us.

For July we’ve chosen Guy Delisle’s Factory Summers. We snagged an exclusive interview with Guy via Zoom, calling in all the way from the South of France where he lives with his wife and two children.

SLB: We really enjoyed Factory Summers! Many of the staff here are visual artists, writers, or musicians, so we related to having to balance a day-job with our artistic interests. Can you talk a little about how you motivated yourself to develop your art while having to work 12 hour shifts?

GD: At the time portrayed in Factory Summers it was just a summer job; I had to juggle more later in my life when I became a fulltime cartoonist. Back then when I worked in the factory I wasn’t really working on anything very serious, maybe just here and there in my free time. After that I was in animation school and had quite a bit of work with school and other projects.

SLB: And now you have two children as well. Perhaps you have some advice about time management for aspiring artists?

GD: It’s funny, when you are young and a bachelor you can work all night and then sleep in the daytime, you can do whatever you want; you have a lot freedom and it’s very fun. I was very creative at that time, working on my own. Back then there was no internet, so you were focused on what you were doing. Not like today!

When you have kids you have to make a shift from the full freedom you might have to basically a 9-5—you have to pick them up at school etc—so you have to work as if you had a regular job. It’s supposed to be creative, but the work needs to get done between certain times. This balance isn’t easy to find. You go to your desk and you know you have a few hours to work so you better get to it. If you are on your own working at home without a studio it can be even harder. I’ve done both. It’s easier when you go somewhere and you have others around you that are working, so you get that feeling that it’s time to work. I found several friends who were opening up an atelier, and I’ve been working with them ever since. I enjoy going somewhere, doing my work, and when I’m back home I don’t really think about it. Otherwise I would be always in my head, always working, and like a zombie at home. I just wouldn’t make the shift; I’d remain in the drawing mood.

SLB: We’ve read Pyongyang and Shenzen and were impressed by a feeling of loneliness and the alienation that comes with the meeting of different cultures. We also felt a different but similar type of alienation in Factory Summers. Would you say that you felt like you didn’t fit in in your hometown or in Quebec in general, and is that connected to your move to France?

GD: No, it’s not connected to when I moved to France; I moved there by chance. I was traveling, backpacking in Europe like lots of Canadians do. I wasn’t expecting to stay that long. I worked in Germany for six months—that was in Berlin, and the Wall was just coming down—and then found a job in France. Animation studios were popping up all the time back then. I wanted to go to Italy but that didn’t work out, so I moved to another part of France and have stayed here ever since. I didn’t expect that!

As for not fitting in, it’s a feeling I have wherever I go. I don’t know how this is reflected in my books because I’m not trying to achieve that on purpose; it just shows through me. It’s like when you go to a museum and look at everything there, then look at the catalogue of the exhibition and realize that you’ve missed a lot of great things. I have that feeling being in many places. I’m in France but I’m not French (I’m from Quebec), but I like that. Back in Quebec, I feel like a foreigner: I have a big French accent now. I see things a bit differently, having spent half of my life here, more like a European. Now Quebec is like an exotic place.

I like to talk about exotic places; what I like most is to make small observations. It’s a family thing; whenever I’m with my brother we look at stuff and say “why does it do this?” and “why does it work like that?” It’s an engineer’s way of looking at the world. I’ve always enjoyed that, and that’s the way I see the world; it’s the way I draw; the style of observation I use is not like literature or poetry, it’s the observation of someone sitting on the corner of a street trying to make a sketch and depict what he sees. As for not fitting in, that probably just comes from the way I tell stories.

SLB: Do you miss living Quebec?

GD: Yeah, once in a while! Though I really enjoy being here in the south of France. It’s beautiful; I live in a small town. But yes, I do miss the way people are, the relaxed Canadian way of being. Once in a while I go back home and think “yeah, this is a nice place.” I miss cross-country skiing in the winter! In Quebec the forests are so big; you can go in the woods and stay for hours without seeing anybody. That’s a great feeling.

SLB: Factory Summers ends with you in animation school in Toronto, and we know that you went on to work in animation. How did you get your career in comics started?

GD: By chance actually. I had moved to France, which is such a great country for comics.

Back then in Quebec there wasn’t a very big scene. These days there’s a very interesting scene with many interesting publishers like Drawn & Quarterly, La Pastèque, Mécanique Générale, Éditions Pow Pow. There wasn’t any of that back then. When I arrived in France it was the beginning of the independent movement with L’Association and Éditions Cornélius. Around the same time Drawn & Quarterly started with their books; they were both doing a similar thing in different parts of the world. When I arrived in France I realized there were some independent comics that I didn’t know about, as they weren’t available in Canada; they were from a small independent publishing house and weren’t available in North America. These guys were making comics that I really enjoyed for people my age who had grown up with comics. I started by sending them a few short stories. They liked it, published one, and I worked with them for a long time doing animations (to earn money), short stories (just for fun), then one book, two books, etc. I wasn’t paid for any of the four books I made with them, there was no way that anyone would get paid for that back then. Now things have changed!

SLB: The book seems to me to be as much about your summer job as your relationship with your Dad. I was moved by the scene at the end when you find your books in his apartment; did you ever have any conversations with him about your work? Did you ever get any insight into what he thought about your art?

GD: That wasn’t entirely planned. At first I thought the main subjects would be the factory and the people in the factory. However, I had to explain that my father worked there (which was the reason I was there) and then I had to explain the relationship I had with him, which was more of a non-relationship. Afterwards I realized that maybe the book is more about him than the factory. Yes, there’s a lot of me and the things I see, but he’s there all the time in the book. It was quite moving to work on these scenes now that he has passed away. He was a strange type of guy. I never had that type of conversation—especially as he got older—a normal type of conversation where you ask him questions. And I never found out if he read any of my books. No idea!

I’ve had a lot of people write me about that. Maybe it has to do with the generation, where Dads were not taking care of their kids as much and were just doing their own thing. Now they are more present—like I am! A lot of people wrote saying “my father was just the same!”

The legendary cartoonist aims his pen and paper toward his high school summer job

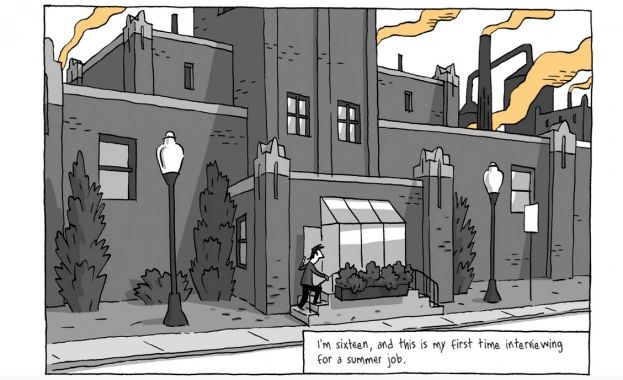

For three summers beginning when he was 16, cartoonist Guy Delisle worked at a pulp and paper factory in Quebec City. Factory Summers chronicles the daily rhythms of life in the mill, and the twelve hour shifts he spent in a hot, noisy building filled with arcane machinery. Delisle takes his noted outsider perspective and applies it domestically, this time as a boy amongst men through the universal rite of passage of the summer job. Even as a teenager, Delisle’s keen eye for hypocrisy highlights the tensions of class and the rampant sexism an all-male workplace permits.

Guy works the floor doing physically strenuous tasks. He is one of the few young people on site, and furthermore gets the job through his father’s connections, a fact which rightfully earns him disdain from the lifers. Guy’s dad spends his whole career in the white collar offices, working 9 to 5 instead of the rigorous 12-hour shifts of the unionized labor. Guy and his dad aren’t close, and Factory Summers leaves Delisle reconciling whether the job led to his dad’s aloofness and unhappiness.

On his days off, Guy finds refuge in art, a world far beyond the factory floor. Delisle shows himself rediscovering comics at the public library, and preparing for animation school–only to be told on the first day, “There are no jobs in animation.” Eager to pursue a job he enjoys, Guy throws caution to the wind.

Born in Québec City, Canada, in 1966, Guy Delisle now lives in the South of France with his wife and two children. Delisle spent ten years working in animation and is best known for his travelogues about life in faraway countries. He is the author of numerous graphic novels and travelogues, including Hostage, Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City and Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea. In 2012, Guy Delisle was awarded the Prize for Best Album for the French edition of Jerusalem at the Angoulême International Comics Festival.